Life, Novels

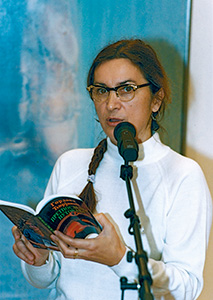

GORDANA ĆIRJANIĆ, WRITER, A LADY OF SEVEN WORLDS

In My Inner Self I’m Always at Home

It is hard for a contemplative person to fit into the world offered today. We are all losers. We are deeply out of step with reason and reality, we are being fed like geese with meaningless contents, anesthetized by served images. Information gained priority over knowledge, entertainment invaded the space of art, the incited market became the only measure of culture. Literary life does not exist, all genuine channels of reception disappeared. However, at all times, the minority preserved the spark, defended the islands of meaning. Ideologies imposed us the dogma that the majority is the measure of all values, even spiritual ones. But it’s not so

By: Branislav Matić

Photo: Guest’s Archive

She is a man-bridge, interpreter of shores. Especially Serbian and Spanish. She scatters hidden images-codes in her novels, hardly audibly sings about inner worlds. She defends herself from organized ”killing of time”, from recycling of the human in the whirlpools of the virtual, by contemplation. The motto of her famous novel What You Have Always Wanted (2010) is the thought of Old Zosima, according to Dostoyevsky: ”Hell is suffering because one cannot love anymore.” She establishes all necessary distances in life and literature with the criteria of value, a specific strictness towards herself and others. She reached the gates of waters through moon’s grass, then further down Velasquez’ Street to the end.

She is a man-bridge, interpreter of shores. Especially Serbian and Spanish. She scatters hidden images-codes in her novels, hardly audibly sings about inner worlds. She defends herself from organized ”killing of time”, from recycling of the human in the whirlpools of the virtual, by contemplation. The motto of her famous novel What You Have Always Wanted (2010) is the thought of Old Zosima, according to Dostoyevsky: ”Hell is suffering because one cannot love anymore.” She establishes all necessary distances in life and literature with the criteria of value, a specific strictness towards herself and others. She reached the gates of waters through moon’s grass, then further down Velasquez’ Street to the end.

Gordana Ćirjanić (Belgrade, 1957), one of the most important Serbian writers today, speaks for National Review.

Threads. When we were little, our mother used to tell my brother and me that we were from a mixed marriage, and then, with certain pride, explained what that meant. Her explanation had nothing to do with what it implies today, and her pride was mainly related to love: there, we are from such distant areas and such distant environments, but still we found each other! Father is from the heart of Šumadija, from the slopes of Rudnik, and mother from Herzegovina, but her family emigrated to Bačka. As children, we went to both sides during the summer, but I preferred staying in the plain, where we played more than in the mountain, because there we had to work as well. It later found its balance in my heart, although I preserved the impression of deep differences in the experience of the world in both lands: seriousness, hardship and gloomy attitude towards life on one side, and socializing, joy and love for narration on the other. There is an explanation for everything, of course. As both sides left a trace inside me, I honored them in a way in my texts. In any case, although I discovered later that the distant ancestors of both my parents were from almost the same place, from Tromeđa, I took my mother’s remark about the mixture as an inexhaustible source of admiration and amazement before the combinatorics of the colorful world. At a mature age, I connected the concept of heritage mainly to language and, in that sense, my first memory is the memory of my mother reading ”Building of Skadar” and me crying inconsolably when they bring young Gojkovica ”her baby in a cradle”.

Threads. When we were little, our mother used to tell my brother and me that we were from a mixed marriage, and then, with certain pride, explained what that meant. Her explanation had nothing to do with what it implies today, and her pride was mainly related to love: there, we are from such distant areas and such distant environments, but still we found each other! Father is from the heart of Šumadija, from the slopes of Rudnik, and mother from Herzegovina, but her family emigrated to Bačka. As children, we went to both sides during the summer, but I preferred staying in the plain, where we played more than in the mountain, because there we had to work as well. It later found its balance in my heart, although I preserved the impression of deep differences in the experience of the world in both lands: seriousness, hardship and gloomy attitude towards life on one side, and socializing, joy and love for narration on the other. There is an explanation for everything, of course. As both sides left a trace inside me, I honored them in a way in my texts. In any case, although I discovered later that the distant ancestors of both my parents were from almost the same place, from Tromeđa, I took my mother’s remark about the mixture as an inexhaustible source of admiration and amazement before the combinatorics of the colorful world. At a mature age, I connected the concept of heritage mainly to language and, in that sense, my first memory is the memory of my mother reading ”Building of Skadar” and me crying inconsolably when they bring young Gojkovica ”her baby in a cradle”.

Where infinity began. My early childhood took place in Kragujevac and Zemun. My father had a scholarship from Kragujevac ”Zastava” and had to work five years in the factory. His next stop was ”Zmaj” factory in Zemun. In both cities, we lived in the workers’ settlement, in buildings with huge yards for playing. We, children, were in the yard all the time. Those were happy years when time passed slowly. I remember my self-consciousness about the happiness for being a child and my first thoughts about infinity and eternity. Infinity began behind the yard walls, eternity spread until the following school year. I also remember my exceptionally competitive spirit, which led me to my first solitudes. Since no one was able to hit me in the ”between two fires” game, to catch up with me on roller skates or find me in ”hide and seek”, other children sometimes gave up on playing with me or continued without me. The family circumstances also influenced the childhood feeling of being special. We traveled more than others. My parents would pack us in the ”Cinquecento”, put a tent into the trunk, and travel through Yugoslavia and other countries. Already at the age of five, I visited Austria, Czechoslovakia, Italy. This was in the early sixties, when hardly anyone travelled, let alone in that way. Furthermore, my parents believed that the most important thing in bringing up children was to encourage them to become independent as early as possible. Consequently, I remember that, already in the second grade, I went to music school alone, two stations by trolleybus. My mother worked as well, so the responsibility for ordinary things in life was implemented very early.

Where infinity began. My early childhood took place in Kragujevac and Zemun. My father had a scholarship from Kragujevac ”Zastava” and had to work five years in the factory. His next stop was ”Zmaj” factory in Zemun. In both cities, we lived in the workers’ settlement, in buildings with huge yards for playing. We, children, were in the yard all the time. Those were happy years when time passed slowly. I remember my self-consciousness about the happiness for being a child and my first thoughts about infinity and eternity. Infinity began behind the yard walls, eternity spread until the following school year. I also remember my exceptionally competitive spirit, which led me to my first solitudes. Since no one was able to hit me in the ”between two fires” game, to catch up with me on roller skates or find me in ”hide and seek”, other children sometimes gave up on playing with me or continued without me. The family circumstances also influenced the childhood feeling of being special. We traveled more than others. My parents would pack us in the ”Cinquecento”, put a tent into the trunk, and travel through Yugoslavia and other countries. Already at the age of five, I visited Austria, Czechoslovakia, Italy. This was in the early sixties, when hardly anyone travelled, let alone in that way. Furthermore, my parents believed that the most important thing in bringing up children was to encourage them to become independent as early as possible. Consequently, I remember that, already in the second grade, I went to music school alone, two stations by trolleybus. My mother worked as well, so the responsibility for ordinary things in life was implemented very early.

Stranger. Already as a young engineer, my father began doubting the system he originally trusted. It was not the ideas he had a conflict with, but the people and their ethics. I was eleven years old when he decided to sacrifice the comfortableness of a state apartment for professional freedom, so he took a loan and bought a house. This is when our life changed. No one ”normal” entered such expenditures at the time. We stopped travelling and moved to Voždovac. The period of economizing in the family did not hit me. What hit me most was moving to a separate house. I didn’t have a big yard full of children anymore, it was a private yard. It was a crucial moment for me. From an extrovert, I turned into a serious child. They tried to convince me that we were living in a luxurious area, the so-called officer colony, but all in vain. My parents were not snobs either, it just happened that we came there, but, in the seemingly wonderful part of the city, I became lonely. I think that from that moment on I began feeling secluded, even as a stranger, and that such a feeling has been following me to the very day, wherever I go. I never identified myself with a group again, at that time with my class, and that is when I started changing schools. Behind my parents’ back, I finished eighth grade during the summer and enrolled in the first year of gymnasium after seventh grade. Then I spent my second year of high school in Florida, after sending an application to an open competition, and my parents supported me in it, to everyone’s surprise. So, at the age of fifteen, I went to the United States alone. I never related myself to any ”group”, and upon my return to Belgrade, I felt like a stranger again.

Stranger. Already as a young engineer, my father began doubting the system he originally trusted. It was not the ideas he had a conflict with, but the people and their ethics. I was eleven years old when he decided to sacrifice the comfortableness of a state apartment for professional freedom, so he took a loan and bought a house. This is when our life changed. No one ”normal” entered such expenditures at the time. We stopped travelling and moved to Voždovac. The period of economizing in the family did not hit me. What hit me most was moving to a separate house. I didn’t have a big yard full of children anymore, it was a private yard. It was a crucial moment for me. From an extrovert, I turned into a serious child. They tried to convince me that we were living in a luxurious area, the so-called officer colony, but all in vain. My parents were not snobs either, it just happened that we came there, but, in the seemingly wonderful part of the city, I became lonely. I think that from that moment on I began feeling secluded, even as a stranger, and that such a feeling has been following me to the very day, wherever I go. I never identified myself with a group again, at that time with my class, and that is when I started changing schools. Behind my parents’ back, I finished eighth grade during the summer and enrolled in the first year of gymnasium after seventh grade. Then I spent my second year of high school in Florida, after sending an application to an open competition, and my parents supported me in it, to everyone’s surprise. So, at the age of fifteen, I went to the United States alone. I never related myself to any ”group”, and upon my return to Belgrade, I felt like a stranger again.

Discovering the center of the world. My departure to the US meant a turning point in my relation with my brother. Three years older than me, until then he usually treated me as a kid. After being separated for a year, we met as grown-ups, with an awaken self-consciousness, and became best friends. We discovered together many things Belgrade had to offer: first visits to Skadarlija and discotheques, first visits to the FEST, working in amateur theaters. At that time, the trend was to be a straight A student and rascal at the same time. We had a feeling, and rightfully, that Belgrade was the center of the world, and we hanged around it self-assured. It was normal to see the icons of the time, for example Peter Brook. Since I spoke English fluently, they began hiring me for working with foreigners very early, so I ”hung around” with John Updike or Mark Strand, just to mention the most famous names. Belgrade, therefore, offered me the feeling that I was a citizen of the world, and I was treated the same way in French, Spanish and English provinces, where I often traveled, first by train and then by hitchhiking. It was normal for me to take my backpack and start off to an unknown direction, for an uncertain period of time. Some of those journeys were literally initiatory, such as hiking through La Mancha, following the traces of Don Quixote, before I turned twenty. All this made me feel different, but from today’s point of view, it only seems that I was the predecessor of some mass phenomena, which require neither imagination nor courage: youth tourism with backpacks is common today, or the fact that Spain is now organizing hiking tours down the paths of Don Quixote.

Discovering the center of the world. My departure to the US meant a turning point in my relation with my brother. Three years older than me, until then he usually treated me as a kid. After being separated for a year, we met as grown-ups, with an awaken self-consciousness, and became best friends. We discovered together many things Belgrade had to offer: first visits to Skadarlija and discotheques, first visits to the FEST, working in amateur theaters. At that time, the trend was to be a straight A student and rascal at the same time. We had a feeling, and rightfully, that Belgrade was the center of the world, and we hanged around it self-assured. It was normal to see the icons of the time, for example Peter Brook. Since I spoke English fluently, they began hiring me for working with foreigners very early, so I ”hung around” with John Updike or Mark Strand, just to mention the most famous names. Belgrade, therefore, offered me the feeling that I was a citizen of the world, and I was treated the same way in French, Spanish and English provinces, where I often traveled, first by train and then by hitchhiking. It was normal for me to take my backpack and start off to an unknown direction, for an uncertain period of time. Some of those journeys were literally initiatory, such as hiking through La Mancha, following the traces of Don Quixote, before I turned twenty. All this made me feel different, but from today’s point of view, it only seems that I was the predecessor of some mass phenomena, which require neither imagination nor courage: youth tourism with backpacks is common today, or the fact that Spain is now organizing hiking tours down the paths of Don Quixote.

Being a poet. It could be said that my generation story practically does not exist, due to the fact that I hurried to be the first to experience everything. I don’t know whether it was good, but that is how it was. For example, my generation thinks of itself as the rock generation, which I couldn’t say for myself. I passed the rock period very quickly, in the States, at its source, and it held me only two or three more years. I refused anything mass and popular, and my choice to study world literature spoke of my orientation towards so-called high culture. I published my first book of poems already as a student, and my poetic comrade was Miloš Komadina. We were connected by deep friendship. All other poets of our generation appeared later and nothing connected me with them: neither a personal relation, nor a poetic orientation, nor a generation approach. When they started writing, we already socialized with much older poets. During the first year of my life as a poet, our university was the kafana. It is possible that, hurrying to grow up, I missed a few things, but I cannot say I regret anything. As soon as I graduated from the university, I went to Split, with the intention to live there, at the seaside, but the adventure lasted only a few months, because I got a call from Ivo Andrić Foundation to start working there. I was the first one who got a job, although that didn’t last long as well. I remember telling my brother to remind me in two or three years to quit my job, because I didn’t want to ”marry” any institution, even such a good and strong one. At the time, a poet could live as a freelancer, poetry was appreciated and intellectual work well paid. In that sense, my role model was my older friend, poet Milutin Petrović.

Being a poet. It could be said that my generation story practically does not exist, due to the fact that I hurried to be the first to experience everything. I don’t know whether it was good, but that is how it was. For example, my generation thinks of itself as the rock generation, which I couldn’t say for myself. I passed the rock period very quickly, in the States, at its source, and it held me only two or three more years. I refused anything mass and popular, and my choice to study world literature spoke of my orientation towards so-called high culture. I published my first book of poems already as a student, and my poetic comrade was Miloš Komadina. We were connected by deep friendship. All other poets of our generation appeared later and nothing connected me with them: neither a personal relation, nor a poetic orientation, nor a generation approach. When they started writing, we already socialized with much older poets. During the first year of my life as a poet, our university was the kafana. It is possible that, hurrying to grow up, I missed a few things, but I cannot say I regret anything. As soon as I graduated from the university, I went to Split, with the intention to live there, at the seaside, but the adventure lasted only a few months, because I got a call from Ivo Andrić Foundation to start working there. I was the first one who got a job, although that didn’t last long as well. I remember telling my brother to remind me in two or three years to quit my job, because I didn’t want to ”marry” any institution, even such a good and strong one. At the time, a poet could live as a freelancer, poetry was appreciated and intellectual work well paid. In that sense, my role model was my older friend, poet Milutin Petrović.

Waking up from Yugoslavism. I was brought up in the spirit of Yugoslavism, and only when I moved to Split in 1981, I realized I was Serbian. I went to ”Logos” publishing house and asked for an editor’s job. They immediately accepted be as a part-time associate, and Šime Vranić, banished from Zagreb as a Maspok member, called me ”Little Serb”. I remember he explained me at the end: it’s not a problem to tell someone he is a Croatian, Bosnian or Montenegrin, but it’s very difficult for me to say Serb. However, you exist and we must get used to it. No one ever treated me badly, but also no one knew what I was doing there, so stories were circling around that I was also banished from Belgrade as a dissident. Nonsense. Nevertheless, I realized there in Split that there is no such thing as Yugoslavism. The fact that I was a Serb was just a given condition up to then, an intimate and unimposing given condition, and the atmosphere in the country in the early eighties indicated that my belonging to a nation could be a problem. In such circumstances, pride appears. My deeper relation towards my homeland became clear to me only after I left it for a longer period of time and went to Spain. I used to compare it with the relation we have towards our parents: in order to determine the measure of our love towards them, it is necessary to move away. And so, after ten years of absence, I returned to Serbia only when people started rushing away from it.

Waking up from Yugoslavism. I was brought up in the spirit of Yugoslavism, and only when I moved to Split in 1981, I realized I was Serbian. I went to ”Logos” publishing house and asked for an editor’s job. They immediately accepted be as a part-time associate, and Šime Vranić, banished from Zagreb as a Maspok member, called me ”Little Serb”. I remember he explained me at the end: it’s not a problem to tell someone he is a Croatian, Bosnian or Montenegrin, but it’s very difficult for me to say Serb. However, you exist and we must get used to it. No one ever treated me badly, but also no one knew what I was doing there, so stories were circling around that I was also banished from Belgrade as a dissident. Nonsense. Nevertheless, I realized there in Split that there is no such thing as Yugoslavism. The fact that I was a Serb was just a given condition up to then, an intimate and unimposing given condition, and the atmosphere in the country in the early eighties indicated that my belonging to a nation could be a problem. In such circumstances, pride appears. My deeper relation towards my homeland became clear to me only after I left it for a longer period of time and went to Spain. I used to compare it with the relation we have towards our parents: in order to determine the measure of our love towards them, it is necessary to move away. And so, after ten years of absence, I returned to Serbia only when people started rushing away from it.

Through the eyeglasses of love. Spain is my second, chosen homeland. My daughter is half Spanish. I met her father in Madrid, following the traces of Ivo Andrić. I went to a study trip and stayed there ten years, until the death of my husband Hose Antonio Novais. I would say that I always felt nostalgic about that country, as if I was Spanish in a previous life. Perhaps it was also the influence of the Spanish Civil War myth, the attractiveness of chiaroscuro: the bright aureole of losing on one side and the shadow of isolation on the map of Europe on the other. I learned Spanish at the university, and, of all the literature in the world, chose Don Quixote for my first seminar paper. Being there, I had the privilege to be led through Spanish reality, history and culture by, like Vergil, one of the greatest Spanish reporters, poet and writer, which I absorbed through the eyeglasses of love. An entire life, which, unfortunately, lasted short in real time – a bit less than ten years. My Letters from Spain were created from that bright and exciting period of discovering a country, with constant comparisons with the country I left, a book which certain readers still consider my best work. On my personal path, the death of the man I love was certainly the biggest turning point in life for me: after turbulent experiences I turned to literature and prose, I returned to my country and my language. My first topics in prose were death and a bright land I was already watching from a distance, although I have been constantly returning to it. It could be said that most of my prose texts are an imaginary bridge between Spain and Serbia.

Through the eyeglasses of love. Spain is my second, chosen homeland. My daughter is half Spanish. I met her father in Madrid, following the traces of Ivo Andrić. I went to a study trip and stayed there ten years, until the death of my husband Hose Antonio Novais. I would say that I always felt nostalgic about that country, as if I was Spanish in a previous life. Perhaps it was also the influence of the Spanish Civil War myth, the attractiveness of chiaroscuro: the bright aureole of losing on one side and the shadow of isolation on the map of Europe on the other. I learned Spanish at the university, and, of all the literature in the world, chose Don Quixote for my first seminar paper. Being there, I had the privilege to be led through Spanish reality, history and culture by, like Vergil, one of the greatest Spanish reporters, poet and writer, which I absorbed through the eyeglasses of love. An entire life, which, unfortunately, lasted short in real time – a bit less than ten years. My Letters from Spain were created from that bright and exciting period of discovering a country, with constant comparisons with the country I left, a book which certain readers still consider my best work. On my personal path, the death of the man I love was certainly the biggest turning point in life for me: after turbulent experiences I turned to literature and prose, I returned to my country and my language. My first topics in prose were death and a bright land I was already watching from a distance, although I have been constantly returning to it. It could be said that most of my prose texts are an imaginary bridge between Spain and Serbia.

Out of step with reason. It is difficult for a contemplative person to fit into the world offered today. We are all losers. We are living out of step with reason and reality, already reconciled with the fact that we are being fed, like geese, with contents which have nothing to do with our own life and needs. Gradually, as if tricking us, our life became virtual as well, since we are, for a long time already, under anesthesia of images, messages, information we receive served from every single screen. We cannot take our eyes anymore from this and that screen. Like in a dream. The TV screen became like a drum cake: row of refugees or horrors of war, row of our own floods or elections, row of pink reality happening somewhere else, without which we cannot live any longer. The top of the drum cake is the consoling news that we are holding 86th place in the ”World Report on Happiness”, out of a total of 157 surveyed countries. As if it has to do anything with us or anyone else in this planet. We put mobile phones into the hands of our children. It would be good if anyone could say: look, she is getting old and grumpy about everything, and everything from the past seems better. The problem is that our children are also discouraged and tired like old people, who have already lived their lives. What is the meaning of their youth if they don’t feel the world is theirs? Unfortunately, they also understand time while wandering through the world or staying at home, in the familiar ditch water. And there, at home, we can hardly see anything in the streets, because our eyes are flying towards the colorful billboards, with one of them stating the motto of our time: Everyone wants to be famous. A stupid expression, meaningless, but we were convinced it is true and expresses the spirit of our time, even though we don’t consider ourselves part of ”everyone”.

Out of step with reason. It is difficult for a contemplative person to fit into the world offered today. We are all losers. We are living out of step with reason and reality, already reconciled with the fact that we are being fed, like geese, with contents which have nothing to do with our own life and needs. Gradually, as if tricking us, our life became virtual as well, since we are, for a long time already, under anesthesia of images, messages, information we receive served from every single screen. We cannot take our eyes anymore from this and that screen. Like in a dream. The TV screen became like a drum cake: row of refugees or horrors of war, row of our own floods or elections, row of pink reality happening somewhere else, without which we cannot live any longer. The top of the drum cake is the consoling news that we are holding 86th place in the ”World Report on Happiness”, out of a total of 157 surveyed countries. As if it has to do anything with us or anyone else in this planet. We put mobile phones into the hands of our children. It would be good if anyone could say: look, she is getting old and grumpy about everything, and everything from the past seems better. The problem is that our children are also discouraged and tired like old people, who have already lived their lives. What is the meaning of their youth if they don’t feel the world is theirs? Unfortunately, they also understand time while wandering through the world or staying at home, in the familiar ditch water. And there, at home, we can hardly see anything in the streets, because our eyes are flying towards the colorful billboards, with one of them stating the motto of our time: Everyone wants to be famous. A stupid expression, meaningless, but we were convinced it is true and expresses the spirit of our time, even though we don’t consider ourselves part of ”everyone”.

A postcard from an island of happiness. If we would measure the role of culture by the power and influence of the ministry of culture or the contents in the culture pages of the media, the results would be devastating, not only in Serbia. As information gained priority over knowledge, entertainment invaded the space of art, so artists often submit to it: they are chasing a reaction at first glance, because the audience doesn’t have the time to immerse into it. It is our served reality, impossible to sweeten, ever since art began to be evaluated from the highest social instances, without a drop of hesitation, mainly by market measures. On a personal realm, however, culture became an escape from the world, and art an island of happiness where, the author and receiver alike, are bravely isolated and enduring. It doesn’t matter if it’s just a scattered minority! The minority used to preserve the spark at all times. The thing is that ideologies imposed the dogma that the majority is the measure of all values, even spiritual ones, although it’s not so.

A postcard from an island of happiness. If we would measure the role of culture by the power and influence of the ministry of culture or the contents in the culture pages of the media, the results would be devastating, not only in Serbia. As information gained priority over knowledge, entertainment invaded the space of art, so artists often submit to it: they are chasing a reaction at first glance, because the audience doesn’t have the time to immerse into it. It is our served reality, impossible to sweeten, ever since art began to be evaluated from the highest social instances, without a drop of hesitation, mainly by market measures. On a personal realm, however, culture became an escape from the world, and art an island of happiness where, the author and receiver alike, are bravely isolated and enduring. It doesn’t matter if it’s just a scattered minority! The minority used to preserve the spark at all times. The thing is that ideologies imposed the dogma that the majority is the measure of all values, even spiritual ones, although it’s not so.

Obstructions and consequences. As I said, a book is a commodity, and it is hard for a today’s writer to participate in it. There have never been more publishers and less space for decent publishing. Furthermore, all channels of reception disappeared. The only life of a book is to have a brief review-information about it in the daily newspaper, if it ever happens, and the writer will privately receive impressions from a few readers, on the level of ”I like it”. The most important channel of reception, the library network, is also clogged. They succeeded in destroying the path of ”library purchases of books”, which had been built for decades, so even a very popular prose writer cannot count anymore on having their book in libraries, not to speak about poetry and essays. Thus, a writer still writes, but is not willing to publish. Perhaps the most difficult thing for me is when a younger colleague asks for advice about how to find a publisher who will not ask for money for printing his book.

Obstructions and consequences. As I said, a book is a commodity, and it is hard for a today’s writer to participate in it. There have never been more publishers and less space for decent publishing. Furthermore, all channels of reception disappeared. The only life of a book is to have a brief review-information about it in the daily newspaper, if it ever happens, and the writer will privately receive impressions from a few readers, on the level of ”I like it”. The most important channel of reception, the library network, is also clogged. They succeeded in destroying the path of ”library purchases of books”, which had been built for decades, so even a very popular prose writer cannot count anymore on having their book in libraries, not to speak about poetry and essays. Thus, a writer still writes, but is not willing to publish. Perhaps the most difficult thing for me is when a younger colleague asks for advice about how to find a publisher who will not ask for money for printing his book.

About simplicity and depth. At the time I started writing, I believed in the continuity of literature. My first teachers were my professors at world literature, so my first rebellions were against them, because their interpretations sometimes seemed wrong and sometimes scarce. They were good professors, who certainly largely contributed to the sharpening of my view and the fact that I don’t take any text for granted. However, they didn’t succeed in cooling my view with theory enough to lose the potential of a reader’s experience. My first books of poetry were said to be hermetic, and then came a grand opening. My later opinion about a text, that the most difficult thing is to reach simplicity without losing depth, was certainly most influenced by my husband, with whom I learned a lot. A great Spanish intellectual, he was much older than me and I absorbed a lot from his experience: that we shouldn’t ”blow smoke”, that the embrace with the public is illusive and transient, that authentic values are far from the noise of the world. Later, when I started writing a lot, my continuous school was, and still is, translating. By translating writers I choose myself, I constantly learn, or at least sharpen my relation to language and sentence.

***

Life in Titles

Gordana Ćirjanić (Belgrade, 1957) published books of poetry: ”Moon’s Grass” (1980), ”Lady of Seven Sins” (1983), ”At the Gates of Waters” (1988) and ”Bitter Water” (1994). Books of records: ”Letters from Spain” (1995) and ”New Letters from Spain” (2002). Books of stories: ”Down Velasquez’ Street to the End” (1996), ”They Say Eternity Is Long” (2005), ”Caprices and Longer Stories” (2009), ”When the Day Breaks, Split” (2012). Novels: ”The Journey before the Last” (2000), ”House in Puerto” (2003), ”The Kiss” (2007), ”What You Have Always Wanted” (2010), ”The Net” (2013), ”Seven Lives of Princess Smilja” (2015). Winner of a number of prestigious literary awards, from ”Female Pen” (2000, 2007) to NIN Award (2010).

She translated Luis Cernuda, Juan Rulfo, Juan Octavio Prenz, Jose Antonio Marina from Spanish and Oscar Wilde from English.

***

Workshop

– Working on a prose text, especially novel, requests strong discipline. However, when you catch the momentum, the discipline is not difficult, because the idea and path towards the objective pulls you further, and there is no idling, even in your sleep. I believe that the so-called periods of creative idleness are less explainable, when the writer is constantly alert, like a hunter, to catch the idea around which a story begins turning. Then its maturing, almost permanent, when no one else would be capable of detecting a potential in it. I would say that the most important things happen in such idleness. This doesn’t mean that everything is already under control when the work begins, but it is somehow easier; the thoughts begin turning around specific problems, not in the endless space of overall possibilities.

***

Belgrade Now

– Belgrade today is less my city than it used to be, but perhaps that’s natural. I sometimes ask myself what I am doing here, but since within myself I’m always at home, I would probably ask myself the same question if I were anywhere else. The fact is that Belgrade is my choice, and I don’t dream about being somewhere else. However, since there is no literary life in it anymore, and we all know that it used to take place in media desks and kafanas, I have just a few hidden corners for private conversations or mediation. My going out is riding a bike to Ada Ciganlija, where my table, quiet music and a view of the lake wait for me in a friendly bar.